February 14, 2005

A situation where we shouldn't extend movieclip

You know that you can assign an as2 class to any movieclip symbol in the library. If that class extends movieclip, when you attach the symbol, you get an instance of that class. But you don’t even need to attach the symbol. You can just put the symbol on the stage at design time, and that’s enough to materialize that class when the timeline gets to the frame where the movieclip is located. That can be helpful when you are building an interface. You just put, for instance, a movieclip that represents a button on the stage, and *magic*, you have an instance of its associated class.

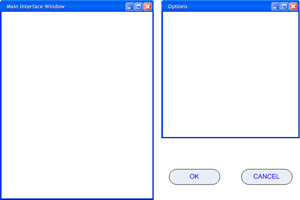

So, imagine you have to create an interface similar to this one:

If we write the following code:

class MyButton extends MovieClip { function MyButton() { stop(); } function onRollOver():Void { gotoAndStop(2); } function onPress():Void { gotoAndStop(3); } function onRollOut():Void { gotoAndStop(1); } }

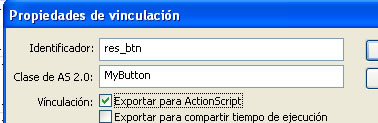

If we assign the movieclip's as2 class to that class:

Then, as soon as those clips appear on the stage, you will have two instances of the MyButton class. Great. We have found an easy way to make the movieclip go to the second frame when we roll the mouse over it, we make it go back to the first frame when we roll the mouse out, and me send it to the third frame when we click it. Easy.

But, our button is not alone, it’s part of an application. What happens when we click it? How does this button interact with the rest of the application?.

Remember, we did not create the instances of MyButton through the constructor, so we cannot pass them any parameters. So, what can we do when we click the button?

Well, we can initialize this class as an event source. So, we could fire an event when the button is clicked.

Suppose there’s a class that contains the logic of the application, or that just acts as the view, it’s the same. Let’s call it AppInstance. That class could be, for example, instantiated in the first frame of root. This class doesn’t know how many buttons there are on the stage, because it doesn’t create them, so it can not register itself as a listener of any event fired by those buttons.

What can we do, then?. Well, we know those buttons are movieclips that are located on root, so we could add a method like this to the MyButton class:

function onRelease( ) { this._parent.doWhatever( ); }

To fire a function named _root.doWhatever, or:

function onRelease( ) { this._parent.appInstance.doWhatever( ); }

To fire the method doWhatever of the appInstance class.

This code smells really bad. Why?. Because of the _parent. You are targeting directly a timeline. What happens if we must load this interface into another swf?. What happens if the application is not called “appInstance”. What if we must pass doWhatever any parameter that indicates which button has been clicked?. This button will only work if it’s placed on a timeline where there’s an object called appInstance.

We have done exactly the same that what we did, ages ago, when we assigned the "on" handlers directly on a script attached to the movieclip.

So what could we do?. Use composition!!.

Take a look at the following class:

class MyButton { private var timeline: MovieClip; private var buttonId: String; private var btMC: MovieClip function MyButton( timeline: MovieClip, buttonId: String ) { this.timeline = timeline; this.buttonId = butonId; this.btMC = this.timeline.attachMovie( this.buttonId, this.buttonId, this.timeline.getNextHighestDepth( ) ); this.initEvents( ); } private function initEvents( ) { var manager: MyButton = this; this.btMC.onRollOver = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 2 ); } this.btMC.onRollOut = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 1 ); } this.btMC.onPress = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 3 ); } this.btMC.onRelease = function( ) { manager.onRelease( ); } } private function onRelease( ) { } }

I’ve attached the movieclip, but I could have passed its reference as a parameter also, something like:

function MyButton( btMC: MovieClip, buttonId: String ) { this.buttonId = butonId; this.btMC = btMC; this.initEvents( ); }

So, the class that represents the application could do something like this

var btOK: MyButton = new MyButton( this.btOK, "btOK" ); var btCancel: MyButton = new MyButton( this.btCancel, "btCancel" ); btOK.addEventListener( "click", this ); btCancel.addEventListener( "click", this );

Where btOk and btCancel are the instance names of both movieclips

So, the clips can be placed on the stage at design time.

Now the button must interact with the rest of the application. So, if will be easy to fire an event.

Maybe we need to fire events from many different classes, so it won’t be a bad idea to write a base class like this one:

class EventDispatcherImpl { function dispatchEvent() {}; function addEventListener() {}; function removeEventListener() {}; function EventDispatcherImpl() { mx.events.EventDispatcher.initialize(this); } }

So, MyButton will be:

class MyButton extends EventDispatcherImpl { private var buttonId: String; private var btMC: MovieClip function MyButton( btMC: MovieClip, buttonId: String ) { this.buttonId = buttonId; this.btMC = btMC; this.initEvents( ); } private function initEvents( ) { var manager: MyButton = this; this.btMC.onRollOver = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 2 ); } this.btMC.onRollOut = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 1 ); } this.btMC.onPress = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 3 ); } this.btMC.onRelease = function( ) { manager.onRelease( ); } } private function onRelease( ) { var eventObject: Object={ target:this, type:'click'} eventObject.buttonId=this.buttonId; dispatchEvent(eventObject); } }

What if you don’t want to fire an event?. The application has created the buttons, so it can register itself as an event listener. Or, if you prefer it, you could have passed the button a reference of the application class ( or even better of the application’s interface ):

var btOK: MyButton = new MyButton( this.btOK, "btOK", this );

So forget about extending EventDispatcherImpl. MyButton will look like this:

class MyButton { private var buttonId: String; private var btMC: MovieClip private var appRef: AppInstance; function MyButton( btMC: MovieClip, buttonId: String, ref: AppInstance ) { this.buttonId = butonId; this.btMC = btMC; this.appRef = ref; this.initEvents( ); } private function initEvents( ) { var manager: MyButton = this; this.btMC.onRollOver = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 2 ); } this.btMC.onRollOut = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 1 ); } this.btMC.onPress = function( ) { this.gotoAndStop( 3 ); } this.btMC.onRelease = function( ) { manager.onRelease( ); } } private function onRelease( ) { this.appRef.doWhatEver( ); } }

Anyway, my point is that there are better solutions that just extending movieclip, and letting flash do the work for us.

Posted by Cesar Tardaguila Date: February 14, 2005 02:28 PM | TrackBackI totally agree - it's often far too easy to extend the MovieClip class to get a desired effect, but this only goes to make your class cumbersome to inherit from later on in development. Composition is the best alternative.

It all comes down the OOP inheritance test: is-a or has-a. Is my object a specialised type of movieclip or am I merely reusing it's functionality? If it's the latter, use composition.

Great article!

Posted by: Paul Neave en: February 14, 2005 04:42 PM